A look at butter...

For many agricultural products, tariffs are higher on the processed good than on the raw material. Such tariff escalation is widely used to protect domestic processors of raw materials from foreign competition. Removal of these tariffs may mean that, while there is no direct impact on the volume or price of the raw material, the processor is no longer able to compete.

In the following summary, we use butter to illustrate some of the ways that can be used in a more in-depth analysis of the agricultural consequences of changes to the international terms of trade for processed products.

Butter price is only one component of the milk price. However, similar analysis of skimmed milk powder protection can be combined to estimate milk price.

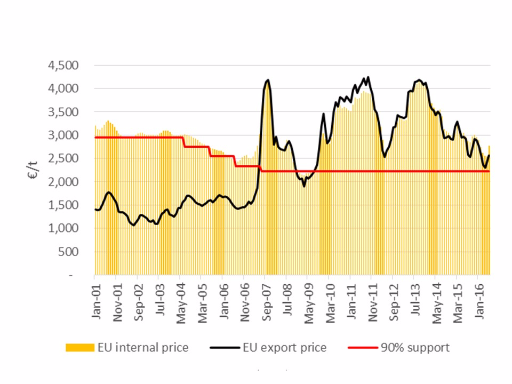

Impact of EU support and change in internal and export prices

Source: AHDB, Bank of England, USDA

Task 1 is to identify the relationship between the EU commodity price and the historic support arrangements. Task 2 is to examine the difference between internal and external EU prices. The graph above describes these relationships.

While butter support has been important historically, it has decreased and the global price has simultaneously increased. The internal EU price now mirrors the external world price.

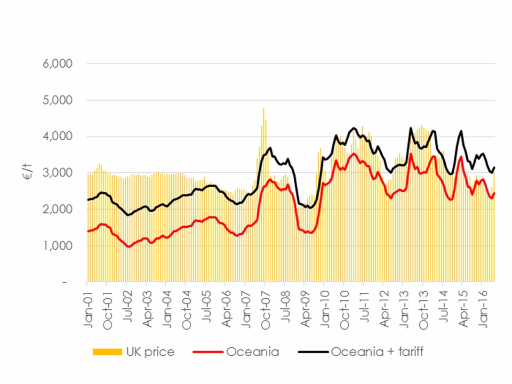

EU price controlled by tariffs

Source: AHDB, Bank of England, USDA

Task 3 is to identify the impact of historic tariffs on the difference between the EU internal prices and the import price, and any anomalies.

New Zealand is granted (what is termed) non-preferential access to the EU market via a Tariff Rate Quota (TRQ) now set at €70/100 kg, well below the general EU tariff of €189.60/100 kg. The total quota is 74,693 t. While historically this was taken up, since 2007 a smaller volume has been imported and New Zealand has remained (in most years) the main non-EU contributor to the EU market. No doubt some imports are due to availability and specific quality attributes at particular times of the year (as also applies to EU exports) but there is a core volume that determines EU butter price. The unusual situation of massive surplus in 2015 and 2016 disrupted the general relationship, by making imports exposed to the tariff expensive, but this is likely to be short lived. The tariff explains most of the difference between the EU and the globally traded price.

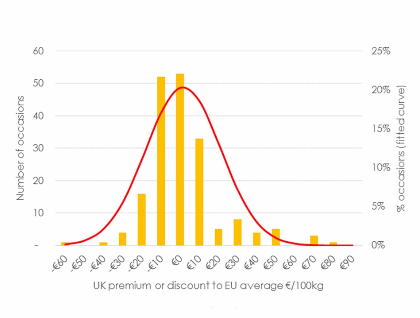

Distribution of UK premium over EU price

Conclusion

The statistics show that while the EU as a whole is a net exporter of butter the UK is a net importer. While the New Zealand TRQ came into being because of the historic relationship between New Zealand and the UK, most UK butter imports now come from the Republic of Ireland. Butter quality varies with time of year and production method so not all butter is the same and some imports may be at a premium. However, the tariff determines the majority of imports and internal price.

Post UK exit from the EU there are a number of possibilities:

- The UK adopts the general third party tariff as currently applied by the EU. This is the most likely outcome at least initially. This is the option under the WTO most favoured nation (MFN) status. Since the general tariff is higher than the TRQ the UK butter price would rise.

- The UK takes a share of the current non preferential EU TRQ with New Zealand. Not all analysts agree that this would be possible but if the object were to minimise distortion it would be to mutual interest. The EU would not be exposed to the same import risk while simultaneously having a larger net export surplus. The UK would have more control to phase in lower tariffs than would be possible by reducing the general tariff (where there is no quota). In this situation UK butter imports from Ireland would be replaced by imports from New Zealand. However, the change in price would be small.

- The UK adopts the EU MFN tariff (with no share of the TRQ) but decides to set the tariff to zero. The zero tariff would have to apply to all countries exporting to the UK. Since New Zealand already supplies to the EU at a lower price than the EU internal price before the application of the tariff, New Zealand or other major exporting countries such as Australia are likely to set the UK price. This would see a fall in UK butter price.

- Despite statements from the NFU (as reported by the Farmers' Weekly) access to the EU through the European Free Trade Area (as exercised by Norway) does not apply to agriculture. Other free trade options may be negotiated but are likely to involve negotiations of a range of industrial and agricultural goods. Trade agreements have been completed within two years (i.e. the period of notice provided under Article 50) and the close historic relationship between the UK and EU makes this possible. It is, however, unlikely without accepting some of the additional political constraints.

Changes in price will also influence the volume of UK production and consumption. While a large rise in the butter price would be expected to direct consumption to other yellow fats reducing demand, preliminary study suggests within the likely price range this would be negligible.

The likely impact on UK butter prices can be estimated and thus the investment risk. The inclusion of other milk components allows an assessment of the impact on milk price. As new announcements are made the anticipated price range can be narrowed.